The Page Amendment is a Trojan horse, cont.

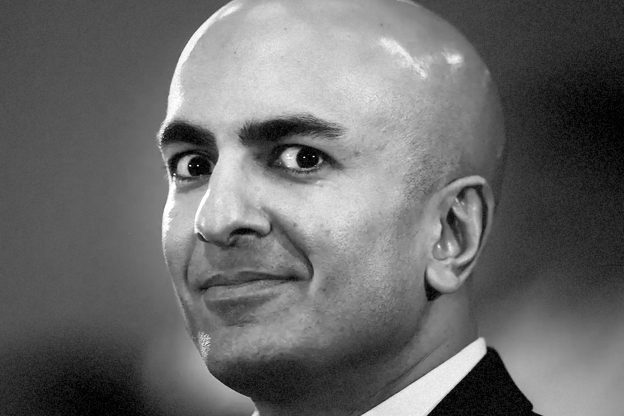

N.B. It’s called the “Page Amendment,” but the real driver behind the initiative is Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank President Neel Kashkari. Before moving to Minnesota, Kashkari, referred to as the “asset manager from Laguna Beach” by the California press, ran for governor of California as a Republican and on an explicitly anti-public school plaform.

Since becoming fed president, Kashkari has had over 400 meetings — his agenda and schedule are public — to discuss “education policy.” He has invested substantial fed resources and personnel in the Page Amendment.

It should be named after him.

– o O o –

I wrote a commentary for the Minnesota Reformer that was published on Monday, March 28th: The Page Amendment is a Trojan horse to destroy public schools. Readers here know that I have written about the Page Amendment before, but just to recap:

You can tell the Page Amendment is a Trojan horse – 11/15/21

Playing with fire – 11/8/21

Misleading at best – 6/8/21

What lies beneath – 5/9/21

Despite all of this, there is more to say about Minnesota’s Education Clause and the Page Amendment. (The Education Clause and the Kash-, sorry, Page Amendment are set out in the Reformer commentary, and other places in the links above as well.)

– o O o –

The equal protection right to a “general and uniform” funded system of public schools contained in the Education Clause is different than protections against discrimination on racial or other protected class grounds under the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. That U.S. Equal Protection Clause is a “must not” clause; the Education Clause in Minnesota is a “must do” clause.

The Education Clause’s protection is an affirmative obligation of the state to establish, maintain, and pay for a “thorough and efficient” system of public education. It protects against discrimination in funding on the basis of race, all right, but it’s broader than that. That was a principle confirmed in Skeen v. Minnesota (1993), discussed in several places mentioned in the links. Skeen wasn’t about race; it was about socio-economic resources available to districts.

Socio-economic factors are also important in a Skeen follow-up case, Cruz-Guzman v. Minnesota, also discussed in the links. The Cruz-Guzman case was decided in favor of the plaintiffs in a reversal by the Minnesota Supreme Court in 2018 (holding that plaintiffs’ claims were justiciable) and was sent back to the lower courts for proceedings in conformity with the Supreme Court’s ruling.

In Skeen, it was rural school districts complaining about inadequate funding compared to some more urban and wealthier ones. In Cruz-Guzman, it’s city parents and students complaining about being deprived of critical funding because of highly-segregated charter schools. The charters are exempt by law from state integration mandates. In the Cruz-Guzman litigation, charter school defendants have argued that if the parents want segregation, what’s the problem?

When we think of segregated charters schools, we think of schools that are almost exclusively Black, Latino, Hmong, or maybe a thinly veiled religious school. Then what about segregated white schools? There are a number of those, too, some with Latin (the mostly dead language, not the ethnic group) names and steeped in “Western civilization.”

This isn’t good for anybody, and going back to Brown v. Board of Education, segregation has been frowned upon. The segregated charter schools put traditional neighborhood public schools into permanent, structural financial crisis. It’s no way to run a railroad unless your intention is to run it off the rails.

A case can be made that the purpose of the Page Amendment is to run public school education off the rails by crippling the Education Clause. Unnecessarily, too, because the current clause already commands the state to provide a quality education to all students. The language in the current clause exists in similar form in many states and has been litigated in them. We know what it means.

There is an extended discussion in the Supreme Court decision in Cruz-Guzman in 2018 about what is required by the Education Clause and the duty of the courts to enforce it. See Section II of that opinion.

The Page Amendment adds nothing but takes something very important away: the language relied up by the Skeen and Cruz-Guzman courts.

One lesson of Skeen and Cruz Guzman is that per pupil funding doesn’t always work for either rural schools or urban ones. When enrollment declines and a district can only support a half a school, it must close the whole school. Rural districts have experienced this acutely for a long time with wave after wave of consolidation. There might be an Education Clause/Skeen remedy here that could address in some measure the additional fixed-per-pupil cost of running a far-flung rural school district.

The Cruz-Guzman plaintiffs obviously believe that the Education Clause and Skeen also have a remedy for their underfunded schools. The common theme in both cases is underfunding.

Next time, I’ll discuss potential remedies under a Page Amendment regime.

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.