Strolling through the garden of logical fallacies – Finis

I won’t even provide the backstory anymore; if you feel the need to catch up, please read part one and part two.

– o O o –

The Page Amendment’s lawyer-cheerleaders assert in their Counterpoint that you either support the amendment or you support the status quo

This is a classic expression of a false dichotomy. Most of you remember George W. Bush’s famous line:

“Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

That was baloney, designed to silence opposition to whatever the U.S. wanted to do. It was effective, though; it shut a lot of people up. The Counterpoint writers are trying to shut people up, too.

The false dichotomy sets up two choices – a good choice and a bad choice – when there are obviously many more choices.

The other choices don’t involve wrapping your arms around public education and jumping off a cliff.

See, I can do it, too.

The Page Amendment will solve racial disparities in education, according to the Counterpoint

This is a great example of begging the question. The Counterpoint does not explain how the Page Amendment will close racial disparities. It’s an absurd assumption, really.

Would it improve disparities by changing the hearts and minds of members of the Minnesota Legislature?

Would it improve disparities because school kids could sue their districts for vouchers for private or religious schools? Even though most kids would remain in public schools that would be bled further white by all those tuition payments to Blake, Benilde St. Margaret, or Our Lady of Grace? (Just to pick on a few on my end of town.)

Well, you get the idea.

Pointing to schools as the source of racial disparities is a red herring

Schools obviously have a role in educating children and a special role in educating children of limited socio-economic means whether Black, Latino, Asian, Indigenous, white, and whether rural or urban. But blaming schools – and especially teachers – for racial disparities is just convenient scapegoating. Solve poverty and you solve education is a quote attributed to NYU Professor and education expert Diane Ravitch. Professor Ravitch and President Obama’s basketball buddy, Arne Duncan, had a dust up about this a decade ago. In a New York Daily News commentary about it, the commentary’s author, John Marsh, said this:

The inconvenient truth: If you care about poverty and economic inequality, you would be better off forgetting about education. Because, even if schools could overcome the effects of growing up in poverty, they cannot reshape the structure of an economy that produces poverty and economic inequality in the first place.

At about the same time, I wrote a story about Arne Duncan: Who’s the bigger data fool (Robert McNamara or Arne Duncan)?

The Legislative Auditor said that our racial disparities were bad, according to the Counterpoint

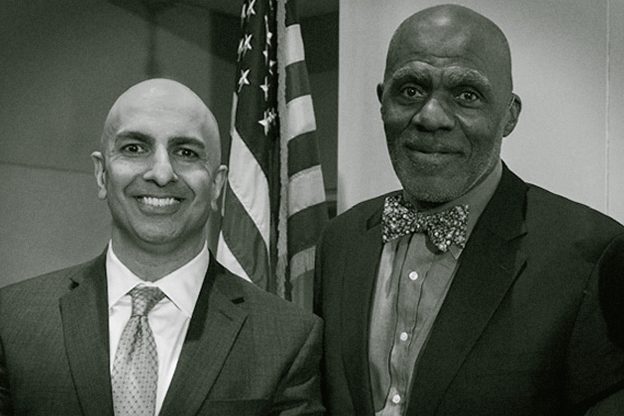

This is an appeal to authority. But the Legislative Auditor’s office did not endorse the Page Amendment as the answer. Only Neel Kashkari and Alan Page can do that!

The Skeen case promises only an adequate education

This is not so much a logical fallacy as a failure to read Skeen v. Minnesota’s majority opinion correctly. There are two issues involved here: the quality of the education required by the Education Clause, and the funding required to deliver it. The Counterpoint confuses the two.

Skeen v. Minnesota confirmed that the Education Clause imposed an affirmative duty on – not just conferred the authority to – the state to provide an education, and to fund it.

First, note that the Education Clause does not use the word “adequate.” It requires an education that furthers the continuance of a functioning republican (meaning representative here) democracy. As I noted in the original Commentary in the Reformer, the plaintiff school districts in Skeen stipulated that they could – did – provide the constitutionally required education to students. The quality of that education was not litigated in Skeen. The use of adequate was more a reference to the adequacy of the funding under the state formula. Some synonyms for adequate are sufficient, enough, requisite, appropriate, suitable, reasonable, and fair.

In addition to stipulating that they delivered a constitutional education, the plaintiff districts also stipulated they had enough money from the state to do it. Not as much as some districts with greater tax capacity, which were able to get operating levy referenda passed more easily, but enough.

We can speculate – maybe even stipulate, so to speak – that Skeen v. Minnesota would have been a different case if the plaintiff districts had come to court prepared to prove that the state formula was not adequate to deliver the constitutionally mandated education and that they weren’t able to provide that education. But they didn’t.

Perhaps the boards of the plaintiff districts thought it politically unwise in their own districts to admit they couldn’t deliver the required education. Maybe they just couldn’t prove it, or they were unprepared to try. Whatever the reason, Skeen is not the poster child for poor education in Minnesota.

There is a recent case, though, that addresses quality of education; it’s the other one I cite frequently: Cruz-Guzman v. Minnesota (2018). Recall that the defendants in Cruz-Guzman, including the charter school defendant-intervenors, said that the courts were not the place to adjudicate school quality issues, that they were not “justiciable.” The Supreme Court said they were:

We cannot fulfill our duty to adjudicate claims of constitutional violations by unquestioningly accepting that whatever the Legislature has chosen to do fulfills the Legislature’s duty to provide an adequate education. If the Legislature’s actions do not meet a baseline level, they will not provide an adequate education. Skeen, 505 N.W.2d at 315; cf. Sheff v. O’Neill, 238 Conn. 1, 678 A.2d 1267, 1292 (1996) (stating that “it logically follows that the education guaranteed in the state constitution must be, at the very least, within the context of its contemporary meaning, an adequate education” and that the government “may not herd children in an open field to hear lectures by illiterates” to fulfill its duty to provide an education (citation omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted)).

We will not shy away from our proper role to provide remedies for violations of fundamental rights merely because education is a complex area. The judiciary is well equipped to assess whether constitutional requirements have been met and whether appellants’ fundamental right to an adequate education has been violated. See, e.g., Rose v. Council for Better Educ., Inc., 790 S.W.2d 186, 212-13 (Ky. 1989); Pauley, 255 S.E.2d at 877-78. Although the Legislature plays a crucial role in education, it is ultimately the judiciary’s responsibility to determine what our constitution requires and whether the Legislature has fulfilled its constitutional duty. [Emphasis added]

That would no longer be true if the Page Amendment came to pass. Proponents of the amendment say it would create a constitutional right, but it really wouldn’t. It just leaves the issue up to the state to establish “uniform achievement standards.” (Which is sort of extra funny, since the web page at Our Children Minnesota rails at some length about the danger of uniformity.)

Recall also that Cruz-Guzman attorney Dan Shulman said in his Commentary in the Reformer that the Page Amendment would knock out the underpinnings of both that case and the Skeen case.

If the Page Amendment is put up for a referendum vote, voters will be asked to give up a constitutional right that courts, around the country, have spent a lot of time considering and defining, for a legislative pig in a poke. I think that’s a bad trade.

Finis

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.