Stephen B. Young’s Magical History Tour

In his op-ed in the Sunday Star Tribune on August 23rd, Stephen Young advances the proposition that the United States was not based on racism, but rather Calvinism. His reasoning perhaps sounds sensible to someone who continues to fight the Vietnam war.

Young’s Calvinism was quite a force for good in history, and especially in the United States. It all began with the foundational document, the Mayflower Compact, which, naturally, was only signed by the men in the company.

This is very standard conservative catechism stuff. You can practically read the Mayflower Compact in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, says Young, and the rest, he continues, is history. Why, Calvinist influence in the north was so great that:

The boundary between the original Plymouth Colony and the original Virginia Colony roughly corresponded to what became the line between the Union and the Confederacy in the Civil War of 1861-1865.

So: Calvinists in the north, no slavery; not-Calvinists in the south, slavery. Pretty simple, right?

Calvinist theology was very special: shining city on a hill and all that, according to Young:

This Calvinist covenant theology carried with it a promise of American exceptionalism — if only Americans would meet their responsibilities.

We all have in our heads the cheering vision of the first Thanksgiving in 1621 with the Pilgrims breaking bread with the natives, the year after the Mayflower company landed in Plymouth. Fewer of us know about this:

The notion of American exceptionalism—that the United States alone has the right, whether by divine sanction or moral obligation, to bring civilization, or democracy, or liberty to the rest of the world, by violence if necessary—is not new. It started as early as 1630 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony when Governor John Winthrop uttered the words that centuries later would be quoted by Ronald Reagan. Winthrop called the Massachusetts Bay Colony a “city upon a hill.” Reagan embellished a little, calling it a “shining city on a hill.”

The idea of a city on a hill is heartwarming. It suggests what George Bush has spoken of: that the United States is a beacon of liberty and democracy. People can look to us and learn from and emulate us.

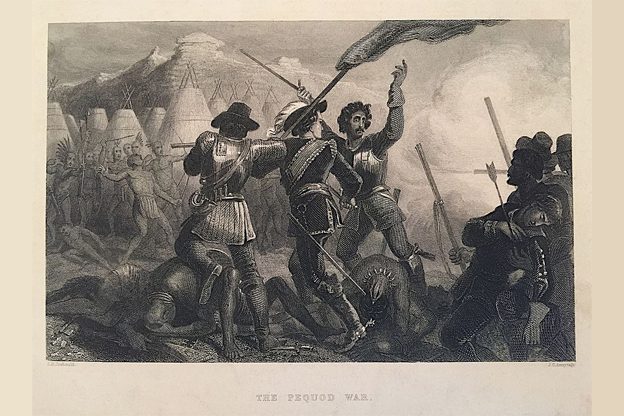

In reality, we have never been just a city on a hill. A few years after Governor Winthrop uttered his famous words, the people in the city on a hill moved out to massacre the Pequot Indians. Here’s a description by William Bradford, an early settler, of Captain John Mason’s attack on a Pequot village.

Those that escaped the fire were slain with the sword, some hewed to pieces, others run through with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatched and very few escaped. It was conceived that they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the praise thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to enclose their enemies in their hands and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enemy.

That’s from Howard Zinn’s 2005 essay, The Power and the Glory, in the Boston Review. It’s one of the better debunking of Stephen Young’s inflated exceptionalism claptrap you’ll find. (I’ve quoted it several times, so it fell easily to hand.)

The event being described was known as the Mystic Massacre.

That charming Calvinist bonfire was just a preface of what was to come, again, from the essay:

Expanding into another territory, occupying that territory, and dealing harshly with people who resist occupation has been a persistent fact of American history from the first settlements to the present day.

And to think, we have the Calvinists to thank for our legacy.

There was another bunch of Calvinists who had the same idea in another part of the world: South Africa, also beginning in the first part of the 17th Century. The Dutch Reformed Church provided theological underpinnings for baasskap and apartheid until 1986. Afrikaner National Party leadership was heavily Dutch Reformed. P.W. Botha was a member of the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk.

So it isn’t just us who have the Calvinists to thank.

The idea that the Pilgrims – the Separatists – and their pals the Puritans (also Calvinists), who came along a little later to beef up the Plymouth Colony, were interested in creating tolerant and liberal communities is laughable. If I set out to pick a group of 17th Century thinkers to demonstrate that the United States didn’t have racist underpinnings, I surely wouldn’t pick the Calvinists.

– o O o –

Update: Reader Alan comments:

Those Massachusetts Bay Colony folks were also known to cut the tongues out of Quakers for espousing a different doctrine and they drove Roger Williams out (to Rhode Island) for the same thing. Tolerance wasn’t exactly their highest calling.

You can read a little about the backsliding Roger Williams here. Among other things, Williams believed in the separation of church and state. If you read the Mayflower Compact that Stephen Young touts, you can see why that was heresy to the Calvinist Pilgrims.

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.