Words designed for eating

As many of you know, friends, word circulated last Thursday that PolyMet’s “water model” for predicting pollution from its proposed open pit mine was, to put it charitably, bogus. To predict pollution for the next 200 to 500 years, a single dry year, 1984, was chosen as the data set. You don’t have to be much of a statistician to see how this might be a problem.

For reasons that are perhaps peculiar only to me, I am reminded of Katherine Kersten. She can cherry pick a fact — or even make one up — and extract from it a stunning rule of universal moral application that sends logic and reason to the showers. It is a gift.

It is a gift she shares with the Minnesota DNR’s Steve Colvin, who said, in response to receiving the news about the model, said, Oh, what the hell; it ain’t no big deal.

“I doubt that it’s a deal breaker at all,” Steve Colvin, who heads the PolyMet review for the DNR, said Thursday. He said it’s not yet clear what impact the flow data will have on the environmental review going forward “but it’s something we’ll have to look at and evaluate.”

Steve is just the kind of public servant upon whom we can rely to protect Minnesota’s patrimony of clean water from the rapacious grasp of the mining companies.

Bwahahahahahahahahaha.

But maybe Steve was just misunderstood.

“I can understand where some of the confusion comes from. In fact, in one of the preliminary drafts we didn’t have the wording quite right on this issue,” said Steve Colvin, deputy director of the DNR’s Division of Ecological and Water Resources who is overseeing the EIS.

They made the embarrassing mistake of telling the truth.

In court, there is a special kind of witness who will say anything — and everything — in the hopes of finding something pleasing to the judge or jury.

These people are known as liars and fools.

A PolyMet spokester, Jennifer Saran, who also possesses Kersten’s gift, said, Well, don’t worry about the time frame; we’ll be around to take care of it.

“The real data [after the mine is dug] will give us a much better idea of what the future looks like,” said Jennifer Saran, PolyMet’s director of environmental permitting and compliance.

She said estimating how long water treatment will be needed is beside the point because the company will offer financial guarantees to treat polluted water — forever if necessary.

“We’re prepared for treating the water for as long as it takes, and financially assuring the money that it would take to treat that water, and we know the treatment works to meet water quality standards so that the time frame is not really something that we have to know,” she said.

And by the time we know the time frame, the PolyMet shell that owns the mining property will be deader than mackerel, or maybe a poisoned walleye or smallmouth bass.

Presently, PolyMet would have trouble guaranteeing a car loan without help from its practical parent, Glencore Xstrata. The idea that PolyMet has the financial strength to insure Minnesota’s clean water into the future is preposterous and laughable. All of PolyMet’s assets are pledged to Glencore for loans it made to PolyMet.

When deciding whether Colvin and Saran should be made to eat their words, consider this: Freedom Industries. Named, apparently, for its ability to dodge environmental responsibilities, it did the only responsible thing when it dumped tens of thousands of gallons of toxic chemicals into the Elk River in West Virginia. It went bankrupt, leaving property owners and water users downstream holding the bag for, including, health problems of people who drink the water, or who have to buy drinking water for an unknown period of time.

And we have another bankruptcy example right here, too, LTV Steel. In fact, the crushing plant that PolyMet owns — and is mortgaged to Glencore — used to be an LTV facility.

LTV Steel Mining Company began operation in 1957 as the Erie Mining Company with strong ties to Cleveland Ohio steel milling interests. LTV is a classic example of the multilayered corporate structures that have dominated the mineral extraction and milling industry. As a separate subsidiary it was designed specifically to run out the marginal iron ore beds lying south and slightly east of the rich deposits of iron ore in Mesabi Range. Once the quality of the ore had played its way out, LTV filed bankruptcy to avoid ongoing liability. Investors made their money and then, through bankruptcy, they were shielding their investments from future liabilities.

Just as PolyMet is designed to shield Glencore Xstrata. The PolyMets of the world even have a special, dismissive name: junior mining companies.

It is apparent that even at this late date, neither PolyMet, nor the people who are supposed to regulate it and keep our water safe, have any understanding of the Pandora’s Box they are about to open.

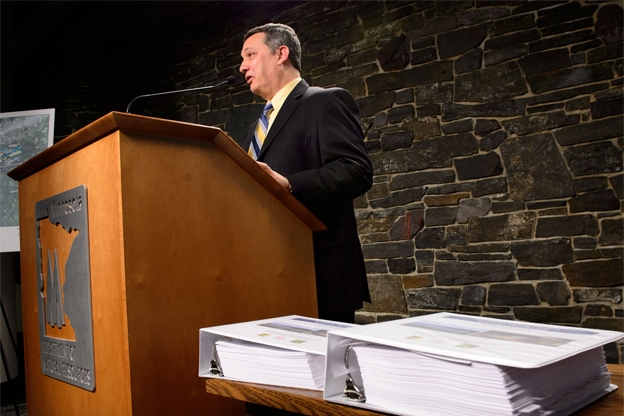

Update Saturday 2/1: At the DNR’s comment session at RiverCentre on January 28th, a member of the DNR’s communications staff pulled me aside and said that I was harsh and personal in my remarks here about Steve Colvin, and I acknowledged that both things were true.

But as I have watched this process unfold, I become less and less sure that the people charged with consideration of permits to mine have a complete understanding of, or a willingness to make a complete accounting of, the environmental, financial, and economic risks to the region and the state, of a sulfide mine.

In fact, I am pretty sure they don’t and won’t. But they’re the same people who will decide when PolyMet has provided sufficient “financial assurances” to protect the state from environmental disaster.

Well, lots luck, friends, lotsa luck.

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.