CCM v. RPM: the hearing II

The airing of the Great Shenanigan

In an earlier post, I recounted the story of the efforts of the Republican Party of Minnesota and its then chairman, Tony Sutton, to hide and then shed $600,000 in debt to three law firms for fees run up in a month for the ill-fated (from the beginning) recount of the gubernatorial contest between Tom Emmer and Mark Dayton, the latter being the guy who currently occupies the corner office at the Capitol. It is a tale of intrigue and despair that I will assume you have read — and you will need to have read to to understand this post.

It is almost two and a half years since the 2010 election that was the subject of the recount. Yet, last Monday, April Fool’s Day [snort], was really the first time that the Great Shenanigan was aired in a public forum. It was in a cramped hearing room at the Office of Administrative Hearings. The issue that remained after the findings of the Campaign Finance and Disclosure Board last summer was: did the RPM, Tony Sutton, the RPM bookkeeper, Ron Huettl, its FEC compliance officer, Dan Puhl, Count Them All Properly, Inc., and the CTAP Board of Director violate Minn. Stat. § 211B.15, subd. 2?

The evidentiary record relied on by both parties was the record produced in the Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board investigation described in the earlier post; neither party called any additional witnesses. The hearing on April 1st was just argument of counsel on that record and the briefing of the parties.

In a nutshell — which is how I know you like to keep this law stuff, kids — the statute cited prohibits business corporations from making “political contributions.” (As opposed to spending for political communication or messaging, which is, of course, permitted after Citizens United.) Sutton tried to raise money and route it through CTAP to pay the lawyers after the RPM filed reports with the Campaign Finance Board omitting the $600,000 debt. And CTAP did pay $27,000 of the RPM’s debt this way.

At the hearing, CCM was represented by Diane Gerth, who laid out the case against the respondents directly and forcefully, although a little less dramatically than depicted by Ken Avidor in his illustration here. The respondents were represented by four lawyers, including Doug Kelley, the assets receiver in the Petters case, and Kevin Magnuson from Kelley’s firm, representing Tony Sutton, Charles Schreffler, representing the bookkeeper, and Richard Morgan, a member of the RPM’s regular cadre of lawyers, on behalf of the RPM.

The defense mounted was a variant of the “Texas cockroach defense,” wherein a defendant or respondent, lacking a genuine substantive defense, just crawls all over the plaintiff or complainant. Sometimes, it even works.

One of the things the defense said was: If we had just set up CTAP as a nonprofit corporation, this would have been okay. And it might have been, if CTAP had been formed at the beginning of the recount and had been the party that hired the lawyers.

Details, details! say the lawyers. A triumph of form over substance! CTAP never made any money!

“A triumph of form over substance,” means here, “Yeah, you got us, but we could have done it right.” It’s not ordinarily a successful argument against a regulator.

One of the other principal arguments was that the CCM complaint was brought more than a year after the formation of CTAP. There is a one-year statute of limitations for bringing complaints under ch. 211B, but there is an important exception when the facts of the violation were concealed by the respondents. That’s clearly the case here: supporters of the party and the public (including CCM) could not have known about the efforts to hide and shed the debt until the CFB made its findings in July of 2012. The CCM complaint was filed shortly after the findings were issued.

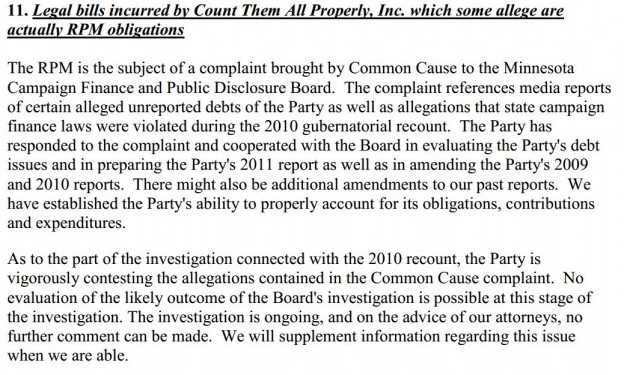

In fact, in the spring of 2011, a committee was appointed by the RPM to look into things, so to speak. It issued a report (not an “audit,” it said) in May of 2012, and this is what it said about the lawyers’ bills:

As of May 2012, the RPM itself was still denying and concealing the facts of the violation. So you see, kids, the statute of limitations defense is a laugher.

The respondents didn’t throw themselves on the mercy of the OAH, but they should have considered it.

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.