Comedy

He who’d make his fellow creatures wise should always guild the philosophic pill.

Gilbert and Sullivan, The Yeoman of the Guard.

One can often say something with a smile or a laugh that would be impossible any other way. You have be communicating with people to make a point to them, and the best way to be sure you are communicating is to make them laugh, because you know you are getting through.

This story is a defense of everyone who uses humor to make a political point, including me, I suppose, but I have Al Franken especially in mind at the moment. There isn’t as much of it going around as the last time Sen. Franken ran, but you still hear comments that he’s not senatorial material because he’s “just a comedian.” The humorless drone Ted Cruz has been flogging the line recently. Al prefers the term “satirist,” understandably.

The best political comedy is aimed at the powerful and the connected. If the target is the poor and disenfranchised, it isn’t comedy. Conservative attempts at comedy, like the cartoons of Glenn McCoy, often come off as racist, misogynist, or just misanthropic.

When Al Franken showed up at a USO show in Iraq clad in a garbage can lids as body armor, he got a big laugh. He delivered a pointed barb at the military brass, and the administration. (Who can forget Donald Rumsfeld’s remark, “You go to war with the army you have, not the one you want.” It was a bloody comment for a war of choice.) The service people in attendance understood it instantly for the moment of subversion it was, and the brass was powerless in the face of it.

It was comedy in service of public policy.

I was rearranging the piles of books around here a few days ago, and I came upon my copy of John Ralston Saul’s The Doubter’s Companion. It’s a dictionary of sorts, kind of an updated version of Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary. I can’t call it indispensable, because I dispensed with it for a few years, but although it is twenty years old now, it is still wickedly funny and spot on. Here’s an excerpt from his definition of comedy:

The least controllable use of language and therefore the most threatening to people in power.

In class-based societies a great deal is made of accents and linguistic formulae. Civilization is then defined as the verbal elegance needed to avoid engaging with other people. Language in such cases is designed to glance off the edges of all important subjects. Comedy is reduced [in these societies] to the harmless elegance of deft and amusing wit.

In contemporary society, respectability is tied to expertise. Subjects are controlled by those who know how to talk about them properly. These DIALECTS of expertise are both obscure and SERIOUS. They require the gravity of the insider. The effect on public debate is to transform any levity into irresponsibility. Almost everyone then feels they must use responsible language when they talk about public questions. Individuals far from power and specialized language try to mouth the formulae of the economists when they talk about debt, as if they were all Cabinet advisers.

In this atmosphere comedy is excluded and reduced to base entertainment intended to distract the non-expert. Television situation comedies are examples of this. Comedy is converted into moralizing belly laughs which reinforces the authority of the controlled, serious, specialized language.

Real comedy doesn’t give a damn about respectability. It belongs neither to a class nor to any interest group and expects to mock power and those who hold it.

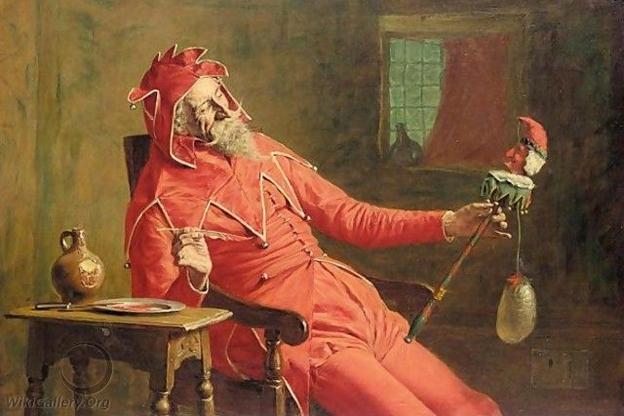

Intelligent mediaeval kings kept court fools to remind them of the natural limits of their unlimited power, but also to prevent the swirling clouds of courtiers from binding them up with obscure servility. The novel first found its role as the most effective device for questioning established power, truths and language through satire, which was often wicked and vicious. Swift, Voltaire, Cervantes, Rabelais and Fielding refused to engage according to the rules. Instead they mocked the established order by removing its protective armour of dignity.

* * *

If writers and readers feel they must act in a respectable manner, then comedy is dead.

Saul, John Ralston (1994). The Doubter’s Companion (pp. 65-67). New York: Simon and Schuster.

(The capitalized words are cross references to other definitions in the book. Saul is a Canadian, which explains the spelling and references to the Cabinet.)

I, for one, would like to see at least a little more of the old Al; he seems awfully confined to quarters these days, and I think unnecessarily so. I mean seriously, if we have to put up with Mike McFadden taking a shot to the nuts, for one of Saul’s belly laughs, we ought to be able to enjoy the occasional witty barb from Al.

Thanks for your feedback. If we like what you have to say, it may appear in a future post of reader reactions.